Americana | Civil War Dates

Our MISSION: To provide accurate information regarding the Civil War timeline with Civil War dates, the Battle of Ft. Sumter and other Civil War battles all with a touch of Americana including Civil War History & memorabilia with quality products that inspire Civil War History buffs and lovers of Americana.

Some Civil War Facts from The Library of Congress:

Civil War Dates: April 12, 1861-April 9, 1865

The Flag of 1865 is available as a mug. See the picture below and click on the link to the right side of it.

Civil War Dates: April 12, 1861-April 9, 1865

The Flag of 1865 is available as a mug. See the picture below and click on the link to the right side of it.

|

Click here for more information of the 36 star American Flag of July, 1865:

https://americana-civil-war-mugs.printify.me/product/544080 |

Civil War Timeline:

November 6, 1860

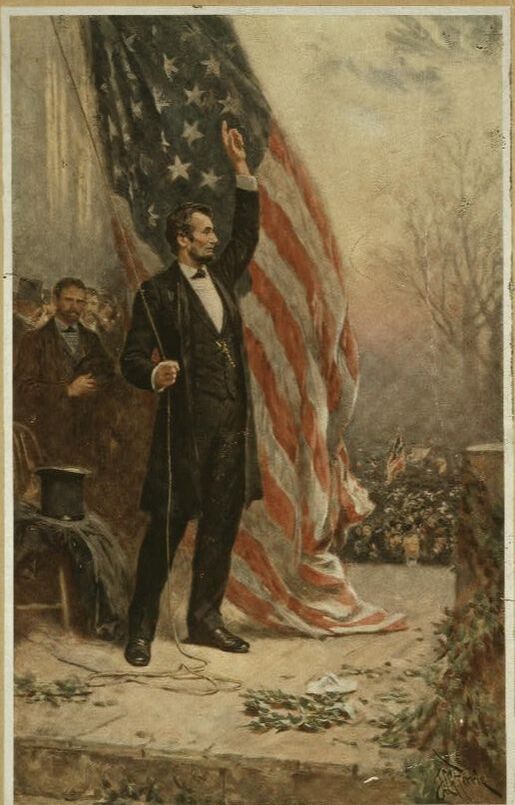

Lincoln elected sixteenth U.S. President

The Prologue:After Abraham Lincoln became president-elect in November 1860, Southern states, economically dependent on slavery, worried that the balance of power in the Union would soon tip irrevocably in favor of the industrial North. To avoid suffering the consequences of such a political shift, Southern states, began to secede, with South Carolina leading the way on December 20, 1860. By February 1, 1861, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had also severed their ties to the United States.

On February 11, 1861, Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln each embarked on a journey that would end in a presidential inauguration. Davis, a West Point graduate and a former U.S. secretary of war and senator, recognized the challenges confronting the government he would lead. The newly formed Confederate States of America (C.S.A.) would need the strength and resources of the eight remaining Southern and border states if it was to succeed as a separate political entity.

Lincoln firmly believed that the Union was fixed and permanent, and it would be his principal duty as president to ensure its preservation. In his inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1861, he went straight to the heart of the nation’s sectional conflict: “One section of our country believes slavery is right, and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong, and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute.”

April 1861–April 1862

Fort Sumter, in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, continued to fly the United States flag, even as Confederate forces surrounded it. Lincoln decided to send provisions but no additional troops or ordnance to the fort unless resistance was met. Unwilling to tolerate a U.S. garrison in Southern territory, Confederates began shelling the fort in the pre-dawn hours of April 12, 1861, and Union guns responded. The Civil War had begun.

As the spring and summer of 1861 wore on, hundreds of thousands of white men, most of them ill-trained and unprepared for war, poured into the armed forces of both sides. Anticipating a day when their services would be accepted, African American men in the North formed military training companies, while women on both sides labored on the home front after their men left for war. Most Americans assumed the war would be over by Christmas, but the bloody battle at Manassas, Virginia, and the Union naval blockade of the Confederate coastline suggested otherwise. As the conflict extended into 1862, the North and South readied their armies for a longer fight.

November 6, 1860

Lincoln elected sixteenth U.S. President

The Prologue:After Abraham Lincoln became president-elect in November 1860, Southern states, economically dependent on slavery, worried that the balance of power in the Union would soon tip irrevocably in favor of the industrial North. To avoid suffering the consequences of such a political shift, Southern states, began to secede, with South Carolina leading the way on December 20, 1860. By February 1, 1861, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had also severed their ties to the United States.

On February 11, 1861, Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln each embarked on a journey that would end in a presidential inauguration. Davis, a West Point graduate and a former U.S. secretary of war and senator, recognized the challenges confronting the government he would lead. The newly formed Confederate States of America (C.S.A.) would need the strength and resources of the eight remaining Southern and border states if it was to succeed as a separate political entity.

Lincoln firmly believed that the Union was fixed and permanent, and it would be his principal duty as president to ensure its preservation. In his inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1861, he went straight to the heart of the nation’s sectional conflict: “One section of our country believes slavery is right, and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong, and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute.”

April 1861–April 1862

Fort Sumter, in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, continued to fly the United States flag, even as Confederate forces surrounded it. Lincoln decided to send provisions but no additional troops or ordnance to the fort unless resistance was met. Unwilling to tolerate a U.S. garrison in Southern territory, Confederates began shelling the fort in the pre-dawn hours of April 12, 1861, and Union guns responded. The Civil War had begun.

As the spring and summer of 1861 wore on, hundreds of thousands of white men, most of them ill-trained and unprepared for war, poured into the armed forces of both sides. Anticipating a day when their services would be accepted, African American men in the North formed military training companies, while women on both sides labored on the home front after their men left for war. Most Americans assumed the war would be over by Christmas, but the bloody battle at Manassas, Virginia, and the Union naval blockade of the Confederate coastline suggested otherwise. As the conflict extended into 1862, the North and South readied their armies for a longer fight.

The Flag of Ft. Sumter is available as a mug. See the picture below and click on the link to the right side of it.

|

Click here for more information of the The Flag of Ft. Sumter:

https://americana-civil-war-mugs.printify.me/product/544068 |

Civil War Timeline con't.

April 1862–November 1862

In spring 1862, the Union Army of the Potomac took the offensive on the Virginia Peninsula, where its ultimate target was Richmond, the Confederate capital. Northern morale was high. Recent Union victories in the West prompted expectations of a similar outcome in the Peninsula Campaign that would lead to a swift and successful end to the war.

As the Army of the Potomac pushed forward, it was hampered not only by Confederate forces but also inclement weather, inferior roads, geographical surprises not indicated on the army’s unsatisfactory maps, and overcautious leadership. It was further hampered by Stonewall Jackson’s spring Shenandoah Valley Campaign and, after June 1, by the skill of the new commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee. After the failure of the Peninsula Campaign, the Union suffered additional disappointing setbacks. General Lee’s first incursion into Northern territory ended with heavy Union and Confederate losses along Antietam Creek near Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862, when more than 23,000 men were killed, wounded, or missing in action in this, the bloodiest one-day battle of the Civil War.

December 1862–October 1863

On January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued the final Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that all slaves within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” Bitterly denounced in the South—and by many in the North—the Proclamation reduced the likelihood that the anti-slavery European powers would recognize the Confederacy as an independent nation and opened the way for large numbers of African Americans to join the U.S. armed forces. At the same time, tensions created by losses on the battlefield and sacrifices on both sides of the home front were reflected in public meetings and demonstrations. Though peace movements were increasing in strength in both the South and North, a majority on both sides remained bitterly determined to pursue the war to victory.

Only two months after the North’s major defeat at Chancellorsville, Virginia, in May 1863, the Union victory at Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863), dramatically raised Northern morale. The fall of Vicksburg, Mississippi, on July 4 militarily split the Confederacy in two—and set Ulysses S. Grant on the path to becoming the Union’s final and most aggressive general-in-chief. In the Confederate states, food shortages and exorbitant prices caused riots in several cities. Rampant guerrilla warfare in Kansas and Missouri created a war within the war.

November 1863–April 1865

On November 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln offered “a few appropriate” remarks at the dedication of a cemetery to fallen Federal troops at Gettysburg. In his brief and eloquent “Gettysburg Address,” Lincoln articulated the purpose of the war and looked beyond it to a time when the nation would once again be made whole.

Yet even greater sacrifice lay ahead. In spring 1864, the Union and the Confederacy plunged into bloody campaigns that inaugurated a fourth year of fighting, prolonging and increasing the horrors of war. Casualty lists had grown to the hundreds of thousands. Civilians on both sides strained to help their governments cope with never-ending waves of the sick and wounded, as well as white and black refugees fleeing before armies or following in their wake. Throughout the year, the Union pursued a “hard war” policy, aimed at destroying all resources that could aid the Rebellion. But the South continued to fight; the end was not yet in sight.

The year 1865 opened with Union victories in the East that closed Lee’s most vital supply line. Further south, U.S. General William T. Sherman’s army stormed out of Georgia and through South Carolina, where Charleston fell in mid-February. By April, Sherman was pursuing Confederates under Joseph Johnston in North Carolina. Lee, unable to hold Petersburg or Richmond, evacuated those cities and was forced to surrender on April 9, 1865. With final victory in sight, Union luminaries gathered on April 14 for a special ceremony at Fort Sumter to again raise the Federal flag. Later that evening actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Epilogue

By May 10, 1865, when U.S. President Andrew Johnson declared armed resistance at an end, vast areas of the South lay in ruins. Four years of brutal combat had taken the lives of an estimated 620,000 Union and Confederate soldiers, shattered illusions, and fueled social reform movements. In the South, the war gave birth to the “Lost Cause” mythology that idealized Southern life and Confederate principles.

Four million Americans who had been considered property in 1860 would be recognized as American citizens with ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. Yet this fact did not erase prejudice. After all eleven Confederate States were readmitted to the Union and the turbulent Reconstruction Era came to a close in 1877, the limited progress some black Southerners had made during the immediate postwar period was largely reversed. It would be more than a century before the promise of equal rights embodied in the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution began to be fully realized.

Yet the Civil War did resolve the primary issues that sparked the conflict. After more than 200 years, slavery was forever outlawed on American soil; and this terrible struggle determined that the great experiment in representative democracy—the United States of America—would not perish from the earth.

April 1862–November 1862

In spring 1862, the Union Army of the Potomac took the offensive on the Virginia Peninsula, where its ultimate target was Richmond, the Confederate capital. Northern morale was high. Recent Union victories in the West prompted expectations of a similar outcome in the Peninsula Campaign that would lead to a swift and successful end to the war.

As the Army of the Potomac pushed forward, it was hampered not only by Confederate forces but also inclement weather, inferior roads, geographical surprises not indicated on the army’s unsatisfactory maps, and overcautious leadership. It was further hampered by Stonewall Jackson’s spring Shenandoah Valley Campaign and, after June 1, by the skill of the new commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee. After the failure of the Peninsula Campaign, the Union suffered additional disappointing setbacks. General Lee’s first incursion into Northern territory ended with heavy Union and Confederate losses along Antietam Creek near Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862, when more than 23,000 men were killed, wounded, or missing in action in this, the bloodiest one-day battle of the Civil War.

December 1862–October 1863

On January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued the final Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that all slaves within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” Bitterly denounced in the South—and by many in the North—the Proclamation reduced the likelihood that the anti-slavery European powers would recognize the Confederacy as an independent nation and opened the way for large numbers of African Americans to join the U.S. armed forces. At the same time, tensions created by losses on the battlefield and sacrifices on both sides of the home front were reflected in public meetings and demonstrations. Though peace movements were increasing in strength in both the South and North, a majority on both sides remained bitterly determined to pursue the war to victory.

Only two months after the North’s major defeat at Chancellorsville, Virginia, in May 1863, the Union victory at Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863), dramatically raised Northern morale. The fall of Vicksburg, Mississippi, on July 4 militarily split the Confederacy in two—and set Ulysses S. Grant on the path to becoming the Union’s final and most aggressive general-in-chief. In the Confederate states, food shortages and exorbitant prices caused riots in several cities. Rampant guerrilla warfare in Kansas and Missouri created a war within the war.

November 1863–April 1865

On November 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln offered “a few appropriate” remarks at the dedication of a cemetery to fallen Federal troops at Gettysburg. In his brief and eloquent “Gettysburg Address,” Lincoln articulated the purpose of the war and looked beyond it to a time when the nation would once again be made whole.

Yet even greater sacrifice lay ahead. In spring 1864, the Union and the Confederacy plunged into bloody campaigns that inaugurated a fourth year of fighting, prolonging and increasing the horrors of war. Casualty lists had grown to the hundreds of thousands. Civilians on both sides strained to help their governments cope with never-ending waves of the sick and wounded, as well as white and black refugees fleeing before armies or following in their wake. Throughout the year, the Union pursued a “hard war” policy, aimed at destroying all resources that could aid the Rebellion. But the South continued to fight; the end was not yet in sight.

The year 1865 opened with Union victories in the East that closed Lee’s most vital supply line. Further south, U.S. General William T. Sherman’s army stormed out of Georgia and through South Carolina, where Charleston fell in mid-February. By April, Sherman was pursuing Confederates under Joseph Johnston in North Carolina. Lee, unable to hold Petersburg or Richmond, evacuated those cities and was forced to surrender on April 9, 1865. With final victory in sight, Union luminaries gathered on April 14 for a special ceremony at Fort Sumter to again raise the Federal flag. Later that evening actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Epilogue

By May 10, 1865, when U.S. President Andrew Johnson declared armed resistance at an end, vast areas of the South lay in ruins. Four years of brutal combat had taken the lives of an estimated 620,000 Union and Confederate soldiers, shattered illusions, and fueled social reform movements. In the South, the war gave birth to the “Lost Cause” mythology that idealized Southern life and Confederate principles.

Four million Americans who had been considered property in 1860 would be recognized as American citizens with ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. Yet this fact did not erase prejudice. After all eleven Confederate States were readmitted to the Union and the turbulent Reconstruction Era came to a close in 1877, the limited progress some black Southerners had made during the immediate postwar period was largely reversed. It would be more than a century before the promise of equal rights embodied in the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution began to be fully realized.

Yet the Civil War did resolve the primary issues that sparked the conflict. After more than 200 years, slavery was forever outlawed on American soil; and this terrible struggle determined that the great experiment in representative democracy—the United States of America—would not perish from the earth.

|

|

|

Something I didn't know until recently:

There were envelopes printed during the Civil War Battles with flags and figures from the Civil War. While the contents of those letters are long gone - my guess they told of love, lack of love, babies, gardens, the weather, and everything that was happening in those days when life was turned upside down for so many - the envelopes live on enamel camp mugs. We have a collection of 30 for your enjoyment. Some were rather faded but nonetheless, tell a tale worth seeing. You can see them and some other civil war mugs here.

There were envelopes printed during the Civil War Battles with flags and figures from the Civil War. While the contents of those letters are long gone - my guess they told of love, lack of love, babies, gardens, the weather, and everything that was happening in those days when life was turned upside down for so many - the envelopes live on enamel camp mugs. We have a collection of 30 for your enjoyment. Some were rather faded but nonetheless, tell a tale worth seeing. You can see them and some other civil war mugs here.